Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks

- Authors: Adam D. I. Kramer, Jamie E. Guillory, and Jeffrey T. Hancock

- Publication, Year: PNAS, June 2014

- Link to Article

Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networksGeneral ApproachResultsAuthors ConclusionsAuthors Comment on Effect Sizes

General Approach

- Two parallel experiments were conducted for positive and negative emotion:

- Exposure to friends’ positive emotional content in ones News Feed was reduced

- Exposure to friends' negative emotional content in ones News Feed was reduced

- Posts were determined to be positive or negative if they contained at least one positive or negative word, as defined by Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count software

- Control conditions for both manipulations were utilized where a similar proportion of positive and negative posts were omitted from ones New Feed

Dependent variables:

- Percentage of positive words produced by a given person

- Percentage of negative words produced by a given person

Secondary measure: testing if the opposite emotional effect is present. I.e. ...

- People in the positivity-reduced condition should express increased negativity

- People in the negativity-reduced condition should express increased positivity

Results

People produced significantly less words after content was omitted from their feed.

This was true for omitting positive as well as negative content

- 99.7% as many words were produced when negative words were omitted

- 96.7% as many words were produced when positive words were omitted

Effect was significantly larger when positive words were omitted...

What are the real world implications of this finding? Does this have any significant meaning?

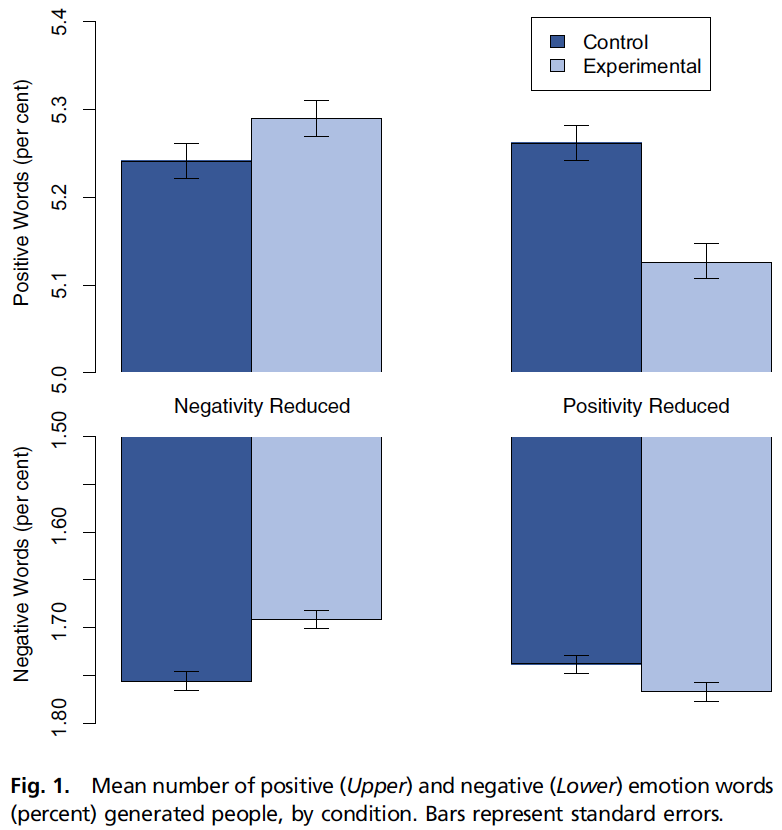

- Reducing positive words in one's News Feed reduced the percentage of positive words in people’s status updates compared with control [t(310,044) = −5.63, P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.02], however, the percentage of words that were negative increased (t = 2.71, P = 0.007, d = 0.001) (Fig 1.)

- Conversely, reducing negative words in one's News Feed reduced the percentage of negative words in people’s status updates compared with control [t(310,541) = −5.51, P < 0.001, d = 0.02] and the percentage of words that were positive increased (t = 2.19, P < 0.003, d = 0.008) (Fig 1.)

Authors Conclusions

The above results provide evidence of emotional contagion. Furthermore,

- Simply failing to “overhear” a friend’s emotional expression via Facebook is enough to buffer one from the effects of emotional contagion.

- Contagion does not require nonverbal behavior, textual content appears sufficient

- Results cannot be attributed solely to the content of the post — i.e. the post contains negative content, as opposed to actual negative emotion

The authors do not actually prove this or even attempt to measure the difference between the two types of content in their study. They simply point to another article which says that negative content is "stronger" than positive content, implying that if people were responding to negative content then they would have seen a stronger effect in their experimental groups who were treated with less positive words in their feeds.

Thus, to me at least, whether their findings are a result of post content as opposed to transference of emotional content from one individual to another is entirely unproven.

Their findings suggest (to me) that they may have simply been manipulating how much good or bad news was circulating in a persons news feed — something that is entirely unsurprising.

Authors Comment on Effect Sizes

Although these data provide, to our knowledge, some of the first experimental evidence to support the controversial claims that emotions can spread throughout a network, the effect sizes from the manipulations are small (as small as d = 0.001). These effects nonetheless matter given that the manipulation of the independent variable (presence of emotion in the News Feed) was minimal whereas the dependent variable (people’s emotional expressions) is difficult to influence given the range of daily experiences that influence mood (10). More importantly, given the massive scale of social networks such as Facebook, even small effects can have large aggregated consequences (14, 15): For example, the well-documented connection between emotions and physical well-being suggests the importance of these findings for public health. Online messages influence our experience of emotions, which may affect a variety of offline behaviors. And after all, an effect size of d = 0.001 at Facebook’s scale is not negligible: In early 2013, this would have corresponded to hundreds of thousands of emotion expressions in status updates per day.

I would agree with the above point if I was confident that what they were measuring was actual emotional expression. Unfortunately, since they don't even attempt to distinguish between genuine emotional expression and literally any other use of vocabulary that may be perceived as having some emotional valence (e.g. news headlines, click-bait article titles, sarcastic comments, etc.), it seems at least possible that they are picking up something else with their measurement.

- I am not too familiar with LIWC2007 but it seems possible that people may utilize language differently on social media when compared to other digital settings.

In my eyes, they leave something to be desired with respect to validating that their measurement of emotional expression — an undoubtedly nebulous thing to measure via digital trace data — is actually picking up signal from what it intends to measure.

Notes by Matthew R. DeVerna